From Overperformance to Exit: A New Framework for High Performer Attrition in Organizations

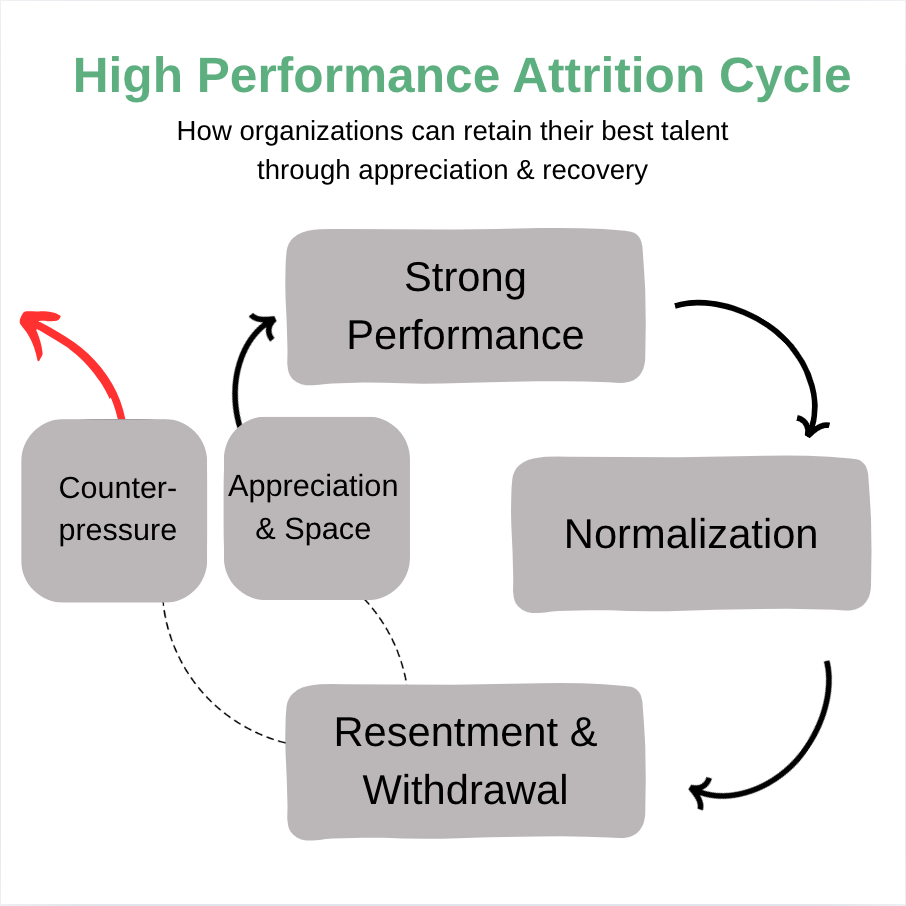

Most companies don’t lose high performers to burnout; they lose them to mismanaged appreciation. Discover the High Performer Attrition Cycle, a new framework that explains how overperformance turns into disengagement, and how authentic recognition and recovery can keep your best people thriving.

ADHD

Jess Sumerak

10/7/20256 min read

Executive Summary

High performers are the engine of organizational success, yet many organizations unwittingly push them toward burnout, disengagement, and attrition. Traditional performance management systems assume human effort is linear and constant, rewarding initial overperformance but failing to sustain it through authentic appreciation and resource replenishment. When effort inevitably ebbs, organizations often respond with pressure, punitive plans, or misdiagnoses of motivation. This paper introduces The High Performer Attrition Cycle, an original framework developed within the Twin Pillars Method that integrates established psychological research with applied organizational practice. The model explains how initial overperformance becomes normalized, how invisible labor leads to resentment and withdrawal, and why authentic appreciation and structured rest, not pressure, are the key interventions.

1. Introduction: The Appreciation Deficit

Organizations celebrate high performance, but few understand how fragile it is without sustained, genuine appreciation. Too often, “recognition” takes the form of generic praise, pizza parties, or scripted “atta boys” at team meetings, gestures that lack emotional resonance and fail to meet employees’ core psychological needs for esteem, belonging, and impact.

In both personal and professional contexts, authentic appreciation is a primary driver of relational trust and intrinsic motivation. Research on gratitude and recognition consistently shows that expressions of genuine appreciation, those that are emotionally grounded and specific, improve well-being, strengthen relational bonds, and boost prosocial behavior (Algoe & Haidt, 2009; Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Renger et al., 2019). Conversely, the absence of appreciation leads to motivational erosion, even among top performers.

This erosion is often invisible at first. High performers tend to set their own bar high, both to meet internal standards and to contribute meaningfully to their teams. Over time, however, their exceptional contributions become normalized. Their output becomes the new baseline, and their discretionary effort fades from view. In place of appreciation, they receive more tasks, tighter deadlines, or nothing at all. What begins as engagement eventually calcifies into quiet frustration.

2. Human Effort: Cyclical, Not Linear

A critical flaw in most performance management philosophies is the assumption of constant output. In reality, human effort ebbs and flows in predictable cycles due to shifting external pressures, personal energy reserves, and resource availability.

The Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 1989) provides a useful lens: individuals seek to build, protect, and replenish personal resources (e.g., time, emotional energy, cognitive bandwidth). When demands exceed resources, performance naturally dips because the individual is conserving or has depleted their internal reserves. Similarly, episodic performance models (Beal et al., 2005) demonstrate that attention and effort fluctuate throughout the day and across weeks in response to both internal states and external stressors.

Recovery is essential. Sonnentag (2003) and Sonnentag and Fritz (2007) found that psychological detachment from work and structured recovery experiences are key predictors of future engagement and performance. Simply put: no one operates at 100% output indefinitely.

When organizations interpret natural performance dips as motivational failures, they often turn to Performance Improvement Plans (PIPs), disciplinary actions, or subtle social exclusion. This misinterpretation sets the stage for the High Performer Attrition Cycle to unfold.

3. The High Performer Attrition Cycle

This original framework, developed through the Twin Pillars Method, integrates insights from organizational psychology, motivational theory, and real-world leadership practice. It explains how initial overperformance transforms into disengagement and eventual exit when organizations fail to provide genuine appreciation and rest.

Stage 1: Initial Overperformance

New employees or high performers begin with exceptional motivation. They are excited, focused, and often produce work far above the team norm. Their discretionary effort is high, and leadership often praises this output initially.

Stage 2: Normalization and Invisible Labor

Over time, this elevated output becomes the new expectation. Tasks that once drew praise become routine. High performers may also receive additional work due to their efficiency. Genuine appreciation fades, replaced by silent reliance.

Stage 3: Resentment and Withdrawal

As energy ebbs (per Beal et al., 2005; Hobfoll, 1989), high performers experience depletion. Without appreciation or recovery time, they begin to conserve energy. Meanwhile, they observe peers contributing less for similar reward, triggering the equity adjustment predicted by Equity Theory (Adams, 1965) and Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954).

Stage 4: Counter-Pressure and Misdiagnosis

Those who benefited from the high performer’s output, leaders, peers, and customers, notice the dip. Rather than recognizing it as a natural cycle, they respond with pressure: formal action plans, gossip, exclusion, or punitive measures. According to Effort–Reward Imbalance theory (Siegrist, 1996), this imbalance between high demands and insufficient rewards leads to emotional strain and withdrawal.

Stage 5: Exit or Recovery

At this stage, two outcomes are likely. If met with authentic appreciation, rest, and structural support, high performers often bounce back, returning to peak output once their resources are replenished (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). If met with continued pressure or lack of recognition, they quiet quit, reduce output permanently, or leave the organization altogether.

4. Why Organizations Misdiagnose the Problem

When high performers decrease their output, many organizations interpret it as a problem of willpower, commitment, or skill, rather than recognizing it as a predictable human pattern. This misdiagnosis stems from several flawed assumptions:

- Linear Output Bias: The belief that performance should increase continuously or remain constant over time, ignoring resource cycles and natural ebbs (Beal et al., 2005; Hobfoll, 1989).

- One-Size-Fits-All Performance Norms: High performers are held to their personal peak rather than the team average, often without systemic supports to sustain that level.

- Misplaced Accountability: Leaders often attempt to correct the symptom (reduced output) rather than the cause (lack of authentic appreciation, recovery opportunities, or structural equity).

- Short-Term Pressure Tactics: Performance Improvement Plans (PIPs), informal shaming, or exclusion can temporarily increase effort, but they do so at the cost of rising resentment, burnout, and turnover.

These misdiagnoses reflect organizational blind spots, not employee deficiencies. The problem isn’t that high performers suddenly “stop caring.” It’s that systems fail to support the recovery and recognition required to sustain exceptional performance over time.

5. Breaking the Cycle: Practical Solutions for Leaders and Teams

Institutionalize Authentic Appreciation

Recognition must be emotionally grounded, specific, and consistent. Be specific, make it relational, and avoid over-reliance on rituals (Algoe & Haidt, 2009).

Normalize Cyclical Performance

Leaders must accept that performance ebbs are natural. Build recovery cycles into workloads and train managers to see dips as signals to replenish resources (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007).

Recalibrate Equity and Expectations

Prevent high performers from leveling down to team baselines through structural equity. Use transparent performance metrics, match rewards to output, and avoid informal over-reliance on top performers (Adams, 1965; Festinger, 1954).

Replace Pressure with Partnership

When performance dips, partner with employees rather than pushing them. Conduct appreciation-centered check-ins and avoid framing dips as moral failings.

Integrate Appreciation into Systems, Not Just Leaders

Sustainable change requires more than good managers. Build appreciation into performance reviews, peer feedback systems, and leadership KPIs (Renger et al., 2019).

6. Conclusion

High performers represent a small percentage of the workforce but generate disproportionate value. Yet many organizations unknowingly burn out or lose their best people by misunderstanding the dynamics of human effort and appreciation.

The High Performer Attrition Cycle offers a new framework: Recognize that overperformance creates expectations that, if unsupported, will erode motivation. Understand that human effort is cyclical, not linear. Replace pressure with authentic appreciation and structured rest. Level teams upward through equity and transparent systems rather than dragging high performers down.

These principles, integrated into the Twin Pillars Method, provide leaders with a practical, psychologically grounded approach to retain peak performers and build sustainable high-performing teams. By accepting the natural rhythms of human work and embedding true appreciation into organizational culture, we can move from reactive performance management to proactive performance stewardship.

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299.

Algoe, S. B., & Haidt, J. (2009). Witnessing excellence in action: The ‘other-praising’ emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(2), 105–127.

Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barros, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (2005). An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1054–1068.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

Renger, S., Miché, M., & Casini, A. (2019). Professional recognition at work: The protective role of esteem, respect, and care for burnout among employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(11), 879–885.

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27–41.

Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 518–528.

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204–221.

Intentional Empowerment, LLC

Empowering people-first, Research based, business strategy & employee well-being

© 2025 Intentional Empowerment. All rights reserved.

Follow us on social

Have a question? We're here to help.

📧 jessicasumerak@gmail.com

📍 Twinsburg, OH (Serving clients nationwide)